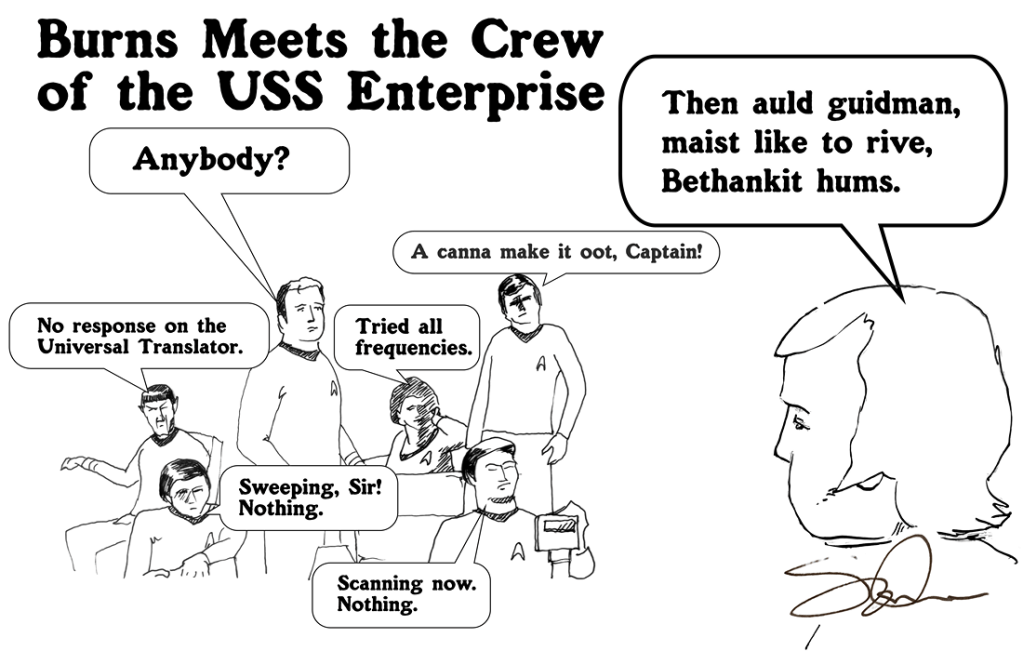

Robert Burns is Scotland’s national bard, yet who among us can understand his poetry? (I was musing over my inability to understand it compared with the advanced capability of, for example, the Star Trek crew to translate it.) It’s a reasonable question to ask since it’s Burns Day today. And also because Scots (and Gaelic) is now, through the Scottish Languages Act 2025, given official recognition by the Scottish Government. Yet another reason to pose the question is that I hadn’t much of a clue of what Burns was saying when I was reading through a book of his poetry recently. Burns spoke Scots, but do people still speak it today? Do people understand it?

Robert Burns, the Ploughman Poet

Let’s start with his Genius Fan pedigree: Rabbie, as we call him here in Scotland, is a right good Eighteenth century fella. Huzzah! He was born on 25 January, 1759 and died at the very, very young age of 37, on 21 July, 1796. He was born into a farming family (hence the nickname Ploughman Poet) in the picturesque village of Alloway, Ayrshire.

Burns is credited with helping preserve the Scots language through his poetry and songs. He’ll be forever known, across the globe and for as long as this planet exists, for poems like Tam O’ Shanter, To a Mouse and To a Haggis, and for the songs he wrote, collected and rewrote, such as Auld Lang Syne and Ae Fond Kiss.

Burns’ Day, Burns’ Night, Burns Supper

So it’s Burns’ Day. We usually say Burns’ Night. Some of us might attend a Burns’ Supper, an event celebrating our national Bard and there are Burns Clubs around the world which do the same. The core part of those supper ceremonies is eating the puddin’ Burns made so famous in his poem To a Haggis, which is recited whilst the haggis puddin’ itself is ritually slaughtered, pierced, stabbed and torn apart…before being plated and passed around the company.

Off the top of my head, I suggest not even 9 out of 10 people on the Sauchiehall Omnibus (there’s no such thing, you know that, right?) would have a clue about what Burns was saying in his Haggis poem. I’ve already said he wrote in Scots. I live in Scotland, not far from where he was born, and I don’t hear people speaking like he writes. (That doesn’t mean anything, I hear you cry. “You don’t know everyone in Scotland. You’re not in their homes while they’re talking amongst themselves.” If anyone says that, then they are correct.)

Burns’ Scots language in his poem To a Haggis

The example of Burns speaking in the illustration to this post is two lines from his eight verse poem, To a Haggis (1786). Here’s the whole of the fourth verse:

Then, horn for horn they stretch an’ strive,

Deil tak the hindmost! on they drive,

Till a’ their weel-swall’d kytes belyve

Are bent like drums;

Then auld guidman, maist like to rive,

Bethankit hums.

I chose that verse because it was particularly impenetrable for me. True, there may well be those who understand it on the page without any difficulty. Here’s a translation:

Then spoon for spoon, the stretch and strive:

Devil take the hindmost, on they drive,

Till all their well swollen bellies by-and-by

Are bent like drums;

Then old head of the table, most like to burst,

The grace!’ hums.

(Thanks to Alexandria Burns Club for this translation)

Note: I use the layout, punctuation and spelling for the Scots version of this poem (above) as provided in the Wordsworth edition of the Collected Poems of Robert Burns.

Scots language is now protected by law

So, the Scots (and Gaelic) language is now protected in law. Our MSPs did that. Braw guid. (That’s Scots language for ‘Jolly good’ according to the OpenL Scots-English-Scots AI translator app. I’m chuckling at the silliness of this. I mean, what’s the point? It’s fun to translate rude words and sentences…maybe (I haven’t done that). Who speaks Scots in such a way that they’d need English translated into Scots? Surely that’s not required? Not like they do in the European Parliament, where they translate all documentation into the 24 official languages to meet member needs.

Well, it’s started. Though how far the Scottish Government will go to produce documents in Scots, I don’t know. Visit the Scottish Government’s languages policy intranet pages and you can see it in action. At the top of the page it reads:

The Scots language is an important part of Scotland’s culture and heritage, appearing in songs, poetry and literature, as well as daily use in our communities. In the 2022 census, 1,508,540 people reported that they could speak Scots, with 2,444,659 reporting that they could speak, read, write or understand Scots. As the sole custodian of Scots we have a duty to protect this indigenous language and celebrate its contribution to Scotland’s identity and future.

There’s a link on that page which says Read this page in Scots. And here it is in all its glory:

The Scots leid is a important pairt o Scotland’s cultural heirship, kythin in sang, poyems an leetratur, an in ilka day uiss in oor communities forby. In the 2022 census, 1,508,540 people reportit that they cuid speak Scots, wi 2,444,659 reportin that thay cuid speak, read, write or unnerstaun Scots. As the ae guardian o Scots it faws til us tae gie this hamelt leid beild, an mak namely its pairt in Scotland’s identity noo an in time tae come.

Now I think about it AI can probably translate every document and webpage the Scottish government might produce. If there’s someone out there who’s thinking they have a career as a Scots translator…I think you should retrain. No-one is EVER gonna want anything translated into Scots. Now, translated OUT of Scots and into English, for example…don’t give that to AI. That’s a job for a human, someone who understands the humanity in language, a scholar, an enthusiast. Let’s never have an AI translation of Burns’ poems.

Burns and the Scots language I hear day to day

I use very few Scots words when I speak. I’m kind of an Anglophile. My mother was English and father Scottish, but by an accident of fate I was born in London, while brother and sisters were born in Scotland, where we all then grew up. And because my mother’s family were all in London our family has always had a connection there. We’ve all visited often enough.

The AyeCan.com website, run by the Scots Language Centre, is a great little website that reminds us that we speak Scots. It tells us that we commonly use words like bairn, wean, dreich, brae, heid, doon, aboot, cooncil, hoose, lang, eejit, glaikit, bonnie, ken, fitba, lad, lass, stooshie, stramash, faither, mither, maw, paw….in our everyday speech.

I know those words, I use them for fun or flavour when I’m talking, but they’re not part of my daily language. Yet when I visit my wife’s parents, we all live in South Lanarkshire, most of those words will pop up in any conversation.

Twenty First Century Scots language

When I read Burns (try to read Burns) his Scots language feels like it’s familiar, but I can’t understand it. What’s preventing me from understanding Burns? It’s the words, the imagery/metaphors and the poetry format. That might mean I understand clearly less than 25% of any Burns poem in Scots. But when I visit my parents-in-law they speak I understand 100% of what they say. And they do use words like those mentioned above from the Aye Can website. Does that mean they don’t speak Scots…because I understand them?

I believe that today Scots people speak English, but with local dialects – from Shetland in the north to Kirkcudbright in the south west – that feature heavy accents and often with lots of local words (eg. bairn and weans), but also with recognisable English words that have been stretched in the Scots accent: eg. cooncil, and some grammatical idiosyncracies. So, if I filter out the accent, the commonly used words across Scotland (and many parts of England), the English words that have been Scotified, the grammar which our brains auto-translate, then there’s not much left of the so-called Scots language. In other words, I’m not hearing the Scots language. I’m hearing Scots dialects.

If your average Scots person travelled back in time to Eighteenth century Edinburgh would they know what people were saying? We won’t know, but we do know that contemporary English speakers often found native Scots speakers difficult to understand. The modern Scots person has become an English speaker with an accent and some leftover words, metaphors and grammar from two hundred plus years ago .

Eighteenth century Scots language

Burns’ fellow men and women would have been able to understand that To a Haggis poem, composed in the native Scots language as it was spoken and, if they were able to read (Scotland had very high literacy rate at the end of the Eighteenth century), then also understand it on the page. The poem was first published in Edinburgh’s Caledonian Mercury newspaper on 20 December, 1786.

So, here’s a question: Would Rabbie Burns be understood if he time travelled to the twenty first century? I would argue no. That is, not if he spoke the language he wrote in. Like I said at the start of this post, people I meet wouldn’t understand Burns poetry. But there’s more to language than the words. When someone’s speaking I’m assisted by the context and their body language. My listening French is poor, but it’s helped by the context and the manner of speaking.

Lots of Scots in the Eighteenth century wanted to learn to speak English. James Boswell was just one of many 100s who attended the elocution lectures by the likes of Thomas Sheridan (1719-1788) in Edinburgh in the 1760s. Boswell and many scholars and men of letters were vexed by wanting to learn to speak the English to mix well in London, with their natural love for their country, its ways and language.

People and the Passion for their language

Scots people are passionate about the way they speak. Like all people, I suppose. In Britain we enjoy trying to pinpoint a person’s home by the way they speak, by their accent. We feel like we have more accents than anywhere in the world. I feel like the Scottish Parliament is promoting the Scots language to a role it should no longer have. It’s not like Gaelic, which is unintelligible to non-Gaelic speakers. (Three news articles I read only mentioned Gaelic and overlooked Scots.) We all agree Gaelic’s a language, but I have to be persuaded that Scots is a language, today in the Twenty first century.

But the Scottish Parliament has given Scots language official recognition and that will come with investment. I don’t mind that. There was no Scottish Parliament when Burns was alive – it was dissolved in 1707 with the union of England and Scotland – and power transferred to Westminster in London. Were he alive today, he would most definitely be in favour of a Scottish Parliament. He would have been dismayed that an act of the Scottish Parliament was required to promote the Scots language. Just so that people had a hope of reading his poetry and understanding it.

Do you know Shetland word ‘knapping’ (pronounced kuh-nappin’)? It means switching from a local dialect to English when speaking to someone who doesn’t speak the local lingo. When enough Eighteenth century Scots did that often enough, the Scots language was doomed.

But it looks like we won’t have to wait until the Star Trek era to get Spock’s Universal Translator…since AI’s already giving us live translations of texts in our mobile phones. The Babel fish of Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is with us now. In our pockets.

Notes

Collected Poems of Robert Burns, Intro by Tim Burke (1984) Wordsworth Poetry Library

Eighteenth century fans: Leave your comments here