Novelist Fanny Burney shared a friendship with one of the Eighteenth century’s greatest writers, Samuel Johnson, and when she died in 1840, at the age of 87, the mighty Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote of his surprise that someone who mixed in the illustrious Johnson circle, so many years ago, had only just passed away.

The news of her death carried the minds of men back at one leap over two generations, to the time when her first literary triumphs were won… Thousands of reputations had, during that period, sprung up, bloomed, withered, and disappeared. ‘Madame D’Arblay’, Macaulay (January, 1843)

Fanny Burney, aka Frances Burney, aka Madame D’Arblay led a long life (1752-1840): She wrote four novels (Evelina, published in 1778, was very successful), she became Second Keeper of the Robes to Queen Charlotte (wife of George III – the fella that went mad), as well as Samuel Johnson she became friends with characters such as Joshua Reynolds, Edmund Burke and Hester Thrale, thanks to her father Dr Charles Burney, a respected music historian and musician. She married French exile Alexandre D’Arblay, they lived with their son in Paris for some years, and in 1815 fled to near Brussels from where she heard the cannon at the battle of Waterloo. The family then returned to England to live out their years in Bath.

Fanny Burney’s Mastectomy

Hers is one of three portraits I have on the wall opposite where I write. I was inspired to buy it after I read about her experience of mastectomy, without anaesthetic, in Paris. That was 214 years ago, almost to the day: 30 September, 1811. It’s shocking. Actually, it’s terrifying. Claire Harman, in her book Fanny Burney: A Biography, says: “This blood-curdling description is surely one of the most extraordinary pieces of ‘reminiscence’ ever committed to paper.”

…when the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves – I needed no injunction not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision…

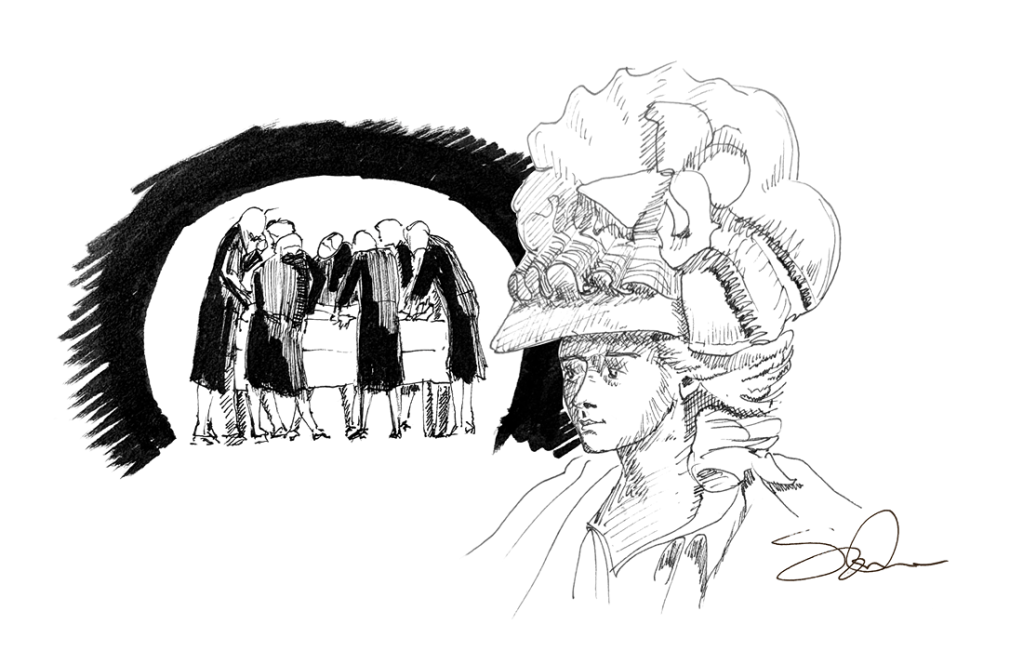

In a July 27, 2000, Independent newspaper review, Loraine Fletcher writes of the prospect of another biography of Burney (Harman’s) just two years after Kate Chisholm’s biography Fanny Burney: Her Life 1752-1840: “Aren’t we Burneyed out? Can we take yet another blow-by-blow account of the seven surgeons in black who surrounded her bed one terrible Paris morning in 1811?” If it’s the same audience that read the two biographies then Harman has to offer something different. Fletcher’s Independent review suggests Harman manages to pull it off.

For me, Burney’s experience under the knife all those years ago makes her memory unforgettable. That’s why I said in a previous post that she has ‘true grit’. That’s my simplistic view, but in her biography Harman suggests there’s a moral in the story: ” It symbolises all the other occasions in her life when she had ‘submitted to the knife’ and bowed to fate or the will of others.”

And she sums up as follows: “…its [the mastectomy narrative] greatest value is as a testimony to the inviolability of the ego.” I think that difficult sentence means that Burney’s account of her mastectomy shows that despite the body being transformed through surgery it doesn’t change the sacredness of the self as an entity. I call it grit.

Notes

Fanny Burney: Her Life 1752-1840, Kate Chisholm (1998)

Fanny Burney: A Biography, Claire Harman (2000)

The Hyacinth Bucket of Eighteenth Century Literature, Loraine Fletcher, Independent (July 27, 2000)

Critical and Historical Essays (Madame D’Arblay), TB Macaulay (1874)

Evelina (or a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World), F Burney (1778)

Eighteenth century fans: Leave your comments here