Ninety five per cent of the books I buy are second hand, and they often have marks of the previous owners – many of whom were libraries. The postie delivered a book the other day, The History of Scottish Literature Volume 2, 1660-1800, and when I opened the cover I saw stamped, in grey ink, the words: ABERDEENSHIRE LIBRARIES WITHDRAWN FROM STOCK. And unusually, a date of return leaf was still attached and in the pocket at the bottom was the book’s ticket. It took me a minute, in conversation with my wife, to recall how this worked, that is, how did the old, pre-computerised library borrowing system work? At the same time I’m re-listening to a favourite book of mine, The Library: A Fragile History, and this time listening out for comments about the systems of ‘issuing’ that have existed over the years. It seems scrolls and books were guarded by the initiated/specialists – for their content, and then protected by owners as signs of belonging to an elite, and then shared among groups for study, but many never returned, and books kept in chests and locked rooms until private libraries appeared and inspection was by permission only, and then in the Eighteenth century membership and subscription libraries, followed by municipal libraries in the nineteenth century. When these libraries popped up, what systems were used to record who borrowed what. (That book’s terrific. I recommend it.)

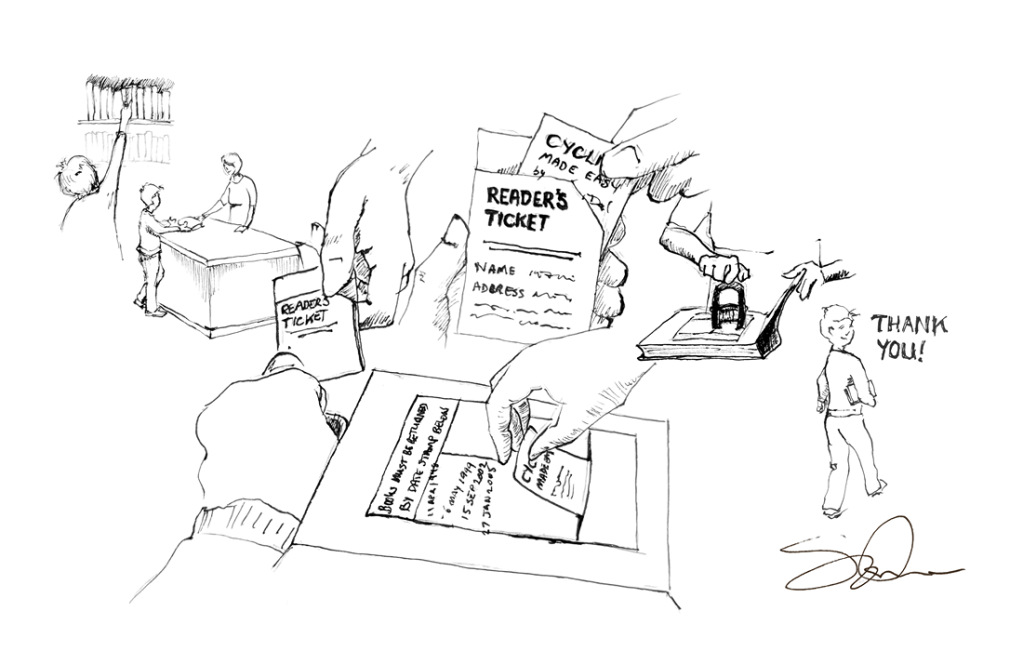

I spent a lot of time on my own in libraries in the 1970s and 80s and this is my recollection of how my borrowing was recorded before computers arrived: I find a book on the shelf that I want and take it to the check out desk. I give the book to the librarian, who takes it, opens the cover and takes out the book ticket. I then present her one of my three library cards (adults got 5 cards). She takes it, puts the ticket (which identifies the book) into my card and places both into a tray, next in line in a day column, labelled two weeks from now. She then takes her ink stamp, which she configured with the date two weeks from today, when she arrived for work that morning before opening. Then she closes the book, looks at me, smiles, hands me the book and I say thanks and walk out. Done. Happy. That’s how I remember it and to see the book ticket and date of return leaf still in place is a real blast from the past.

Notes

The History of Scottish Literature Volume 2, 1660-1800, (ed) Andrew Hook (1987)

The Library: A Fragile History, Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen (2021)

Eighteenth century fans: Leave your comments here