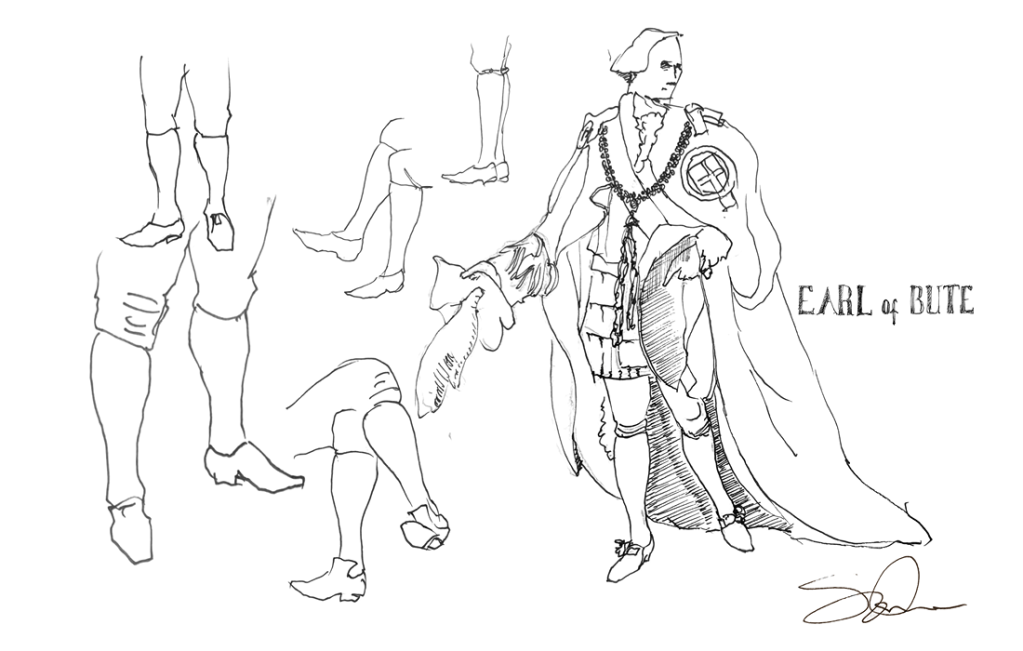

Drawing a gentleman’s leg is one of the many challenges to illustrating scenes from the Eighteenth century. And it’s something to get right – a ‘good leg’ was something for men to show off. The Third Earl of Bute (1713-1792), British Prime Minister from 1762-63, was known for having legs worth looking at and in the 1773 portrait by Joshua Reynolds (see the pic above) his pins are shown to great effect. It’s not just gentlemen, but any man, really. You might have thought it would be the wig or the jacket etc, but I can normally get round them…adequately. Back in the most amazing century ever – the Eighteenth – they didn’t wear long-legged trousers like we do today, they wore breeches that fastened below the knee and stockings of some sort over their foot, lower leg and tied below or above the knee. I can draw men’s legs in trousers – that’s generally a straight leg – but an Eighteenth century leg ‘scene’ is more…anatomical. And since I don’t spend time looking at men’s legs, I struggle to get the shape of the calf, how the lower leg connects to the knee, the bulge of the calf muscle on the outside and the curve on the inside, the position and width of the ankle and of course, the shoes. It all requires practice and I’m rarely one hundred per cent satisfied with the calves I’ve drawn. (Believe me, my sketchbooks have many men’s calves in them.)

An artist who sketches a man’s calf and leg with aplomb is the man who drew the definitive Winnie the Pooh (and all his friends who inhabit 100 Acre Wood) and Mr Toad, Mole, Rat, Badger etc from Wind in the Willows. It’s Ernest Howard Shepard (1879-1976). His fifty four illustrations of James Boswell, Samuel Johnson and many other members of The Club, add energy and real charm to G. Bell and Sons (1930) volume Everybody’s Boswell (it’s an abridged version of Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson. I got my copy for less than a tenner and it’s truly delightful.) A key Shepard skill in illustrating scenes from the Life, scenes that any Boswell or Johnson scholar will recognise, lies in the observation he brings to the scenes. Characters are quite clearly responding to one another, their eye line, expressions and body language all reflect that. His selection of the ‘moment’ within a scene is always spot on, and there’s usually humour or emotion of some sort in the over all narrative of his chosen scenario. Now, when it comes to men’s legs…this is what you all want to know about: Shepard and Eighteenth century men’s legs. Most of his characters are either slim with a healthy, elegant, unremarkable, but simple and narrow leg with a light calf curve rolling into the hem of the breeches, and if the character is fat or stocky, then the leg is short and broad, appearing bulky to the extent the foot is being squeezed into the shoe and the calf so bulky that the hem of the breeches is stretched. All this detail is invisible because of Shepard’s simplicity in sketching and rendering, but it adds volume to the character making his scenes ‘pop’ with vitality. (Shepard also illustrated a volume entitled Everybody’s Pepys, which, if you’re into men’s legs and pen and ink illustration, you might consider buying. It’s on my list. Not because I’m into men’s legs…although I have two of my own.)

Notes

Everybody’s Boswell – Being the life of Samuel Johnson, G.Bell and Sons, Ltd (publ), EH Shepard (illus) (1930)

Everybody’s Pepys: The Diary of Samuel Pepys 1660-1669, OF Morshead (ed), EH Shepard (illus) (1926)

Eighteenth century fans: Leave your comments here