Picture this: the year is 1772, you work as a farrier’s apprentice at a Darlington coaching inn, a lucky appointment because the owner of the inn allows you to read books from his little collection. That’s the year the innkeeper takes ownership of an edition of Oliver Goldsmith’s 1770 poem The Deserted Village. You have the book in hand, open the cover and start to read. You’re about to experience an adventure in imagination. Between the pages of that book are mental images of a life that you’ll recognise. (Never mind the social and political concepts and Goldsmith’s bigger picture.) Goldsmith tells his story in verse, the common format for imaginative composition back then, though the novel was becoming a ‘thing’ by this time. Increasing numbers of people in Eighteenth century Britain were able to read and would find verse in periodicals and books.

You’re not allowed to take the book home; the deal is you have to read it in the busy still room, part of the inn. There’s no Netflix, TV, radio, computers, internet, listening books, LPs, cassettes or MP3 players. Nothing is recorded in 1771, only print. Goldsmith begins his story:

Sweet Auburn! Loveliest village of the plain,

Where health and plenty cheered the labouring swain,

Where smiling spring its earliest visit paid,

And parting summer’s lingering blooms delayed:

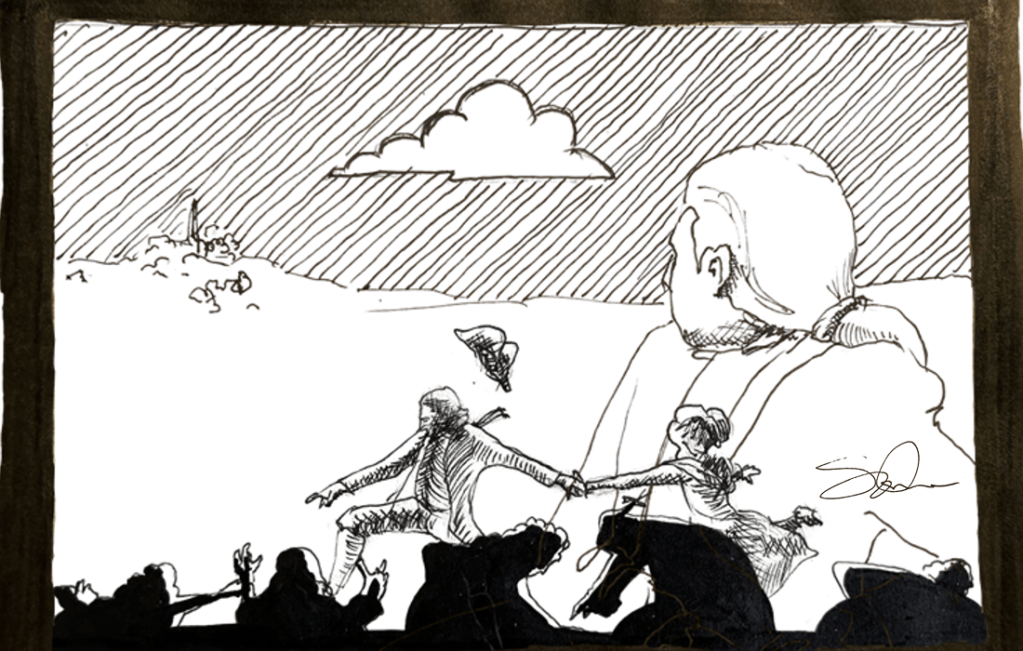

You’re an inexperienced, but enthusiastic reader, and as your fingertip shuffles across the page, you sound out the words. And as you do so, your imagination takes each line of verse and builds a new universe. You’re in an Eighteenth century iMax cinema. Temporarily, you’ve left behind the forge, the horses and your master, the heat and the noise and the smells. What a sensation! Inside your head you’re there, standing in a village called Auburn, looking around you. This is the perfect spot from which to follow Goldsmith’s story. You have only twenty minutes before you have to return to work. Time’s up! You got 34 lines into this 340 line poem. Now, as you return to the bellows, a corner of your mind is exercising thoughts upon the poem, refining the images of everything you read. Thus is poetry the Eighteenth century equivalent of the cinematic experience.

Eighteenth century fans: Leave your comments here