In his brilliant poem To a Haggis, Scots poet Robert Burns introduces us to the family of puddins, of which the haggis is the greatest, the Chieftain. With confidence it rules over all others, including painch, tripe and thairm – all parts of the digestive tract of cattle, sheep and pigs. Let it be known! Its opening verse goes like this:

To a Haggis (full poem at the Scottish Poetry Library)

Fair fa' your honest sonsie face,

Great chieftain o' the puddin'-race!

Aboon them a' ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o' a grace

As lang's my arm.

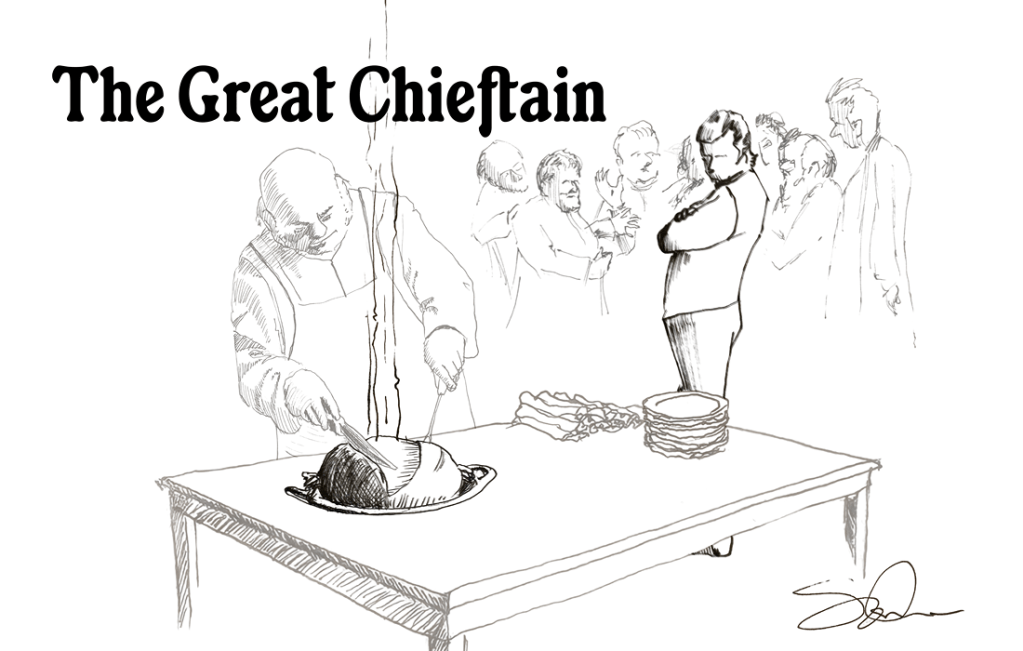

This may be impenetrable to many readers because it’s written in Burns’ native Scots tongue, for example, ‘aboon’ means ‘above’. (Find a parallel ‘translation’ of To a Haggis on the Alexandria Burns Club website.) Burns is Scotland’s national poet and he wrote more than 550 poems and songs. This haggis poem is particularly well-known, or at least the lines of the first verse are well known, because the poem is recited at Burns’ Night celebrations (25 January). At these events, someone stands over the haggis with a raised knife, recites the eight verses praising the “Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race”, and at the final verse the knife is plunged into the haggis. It’s a sacrifice.

Burns (1759-1796) was only 27-years-old when the poem was published in Edinburgh’s Caledonian Mercury newspaper on 20 December, 1786. This was his most productive year for poetry – he wrote 65 poems that year. Think about that. Aged 27! But what were the circumstances in which he wrote the poem? According to the BBC’s excellent Robert Burns hub, it may have been written “on the hoof during a dinner at Mauchline cabinet-maker John Morrison’s house. More likely is the story that the poem had been written by Burns for a dinner at the house of his merchant friend Andrew Bruce.”

Knowing and enjoying haggis as I do, my feeling is that one night Burns saw the perfect haggis, a good looking puddin’ sweating and bulging on a dish (not all haggis look good, for example it’s gotta be sheep’s stomach casing. Not plastic, dear God!), he was taken by its magnificence, his poetical gizmodicals kicked in and, trance-like, he pulled the opening verse out of the ether like Coleridge did with his equally magical Kubla Khan. (Ignore my rhapsodising, but don’t ignore the poem it really is quite inspiring.)

Eighteenth century fans: Leave your comments here